Snake Oil

"Oh, but it's so dreadful," said Marie when I told her to drink her serum.

"It will keep you young," I told her. When I first bought it from a dockside peddler, three bottles and a recipe, he had hissed with a grin, It will keep her young forever.

"What is it even made of?"

"Snake oil and sherry, I believe." I paused. "Nothing dangerous at all."

Marie wrinkled her nose and downed it in one sip. "Absolutely foul. I shan't ever get used to it." She stuck out her tongue in disgust. "You try it."

"I couldn't," I said. "I'm not meant to risk taking any medicines that aren't for me..." She frowned. "And besides, I'd be stealing your youth."

"Oh, that can't be how it works. Just a little sip can't hurt." She picked up the bottle from her bedside and waved it in my face. "You'll need to stay young too, after all."

"I don't think I'll have any trouble doing that," I said with a grim smile. Reluctantly, I took the smallest sip I possibly could. It was as disgusting as Marie had said. I spat it into my empty wine glass when she wasn't looking and crawled into bed, blowing out my candle as I went. "Good night, my love," I said. She kissed me on my cheek.

In the morning she was dead.

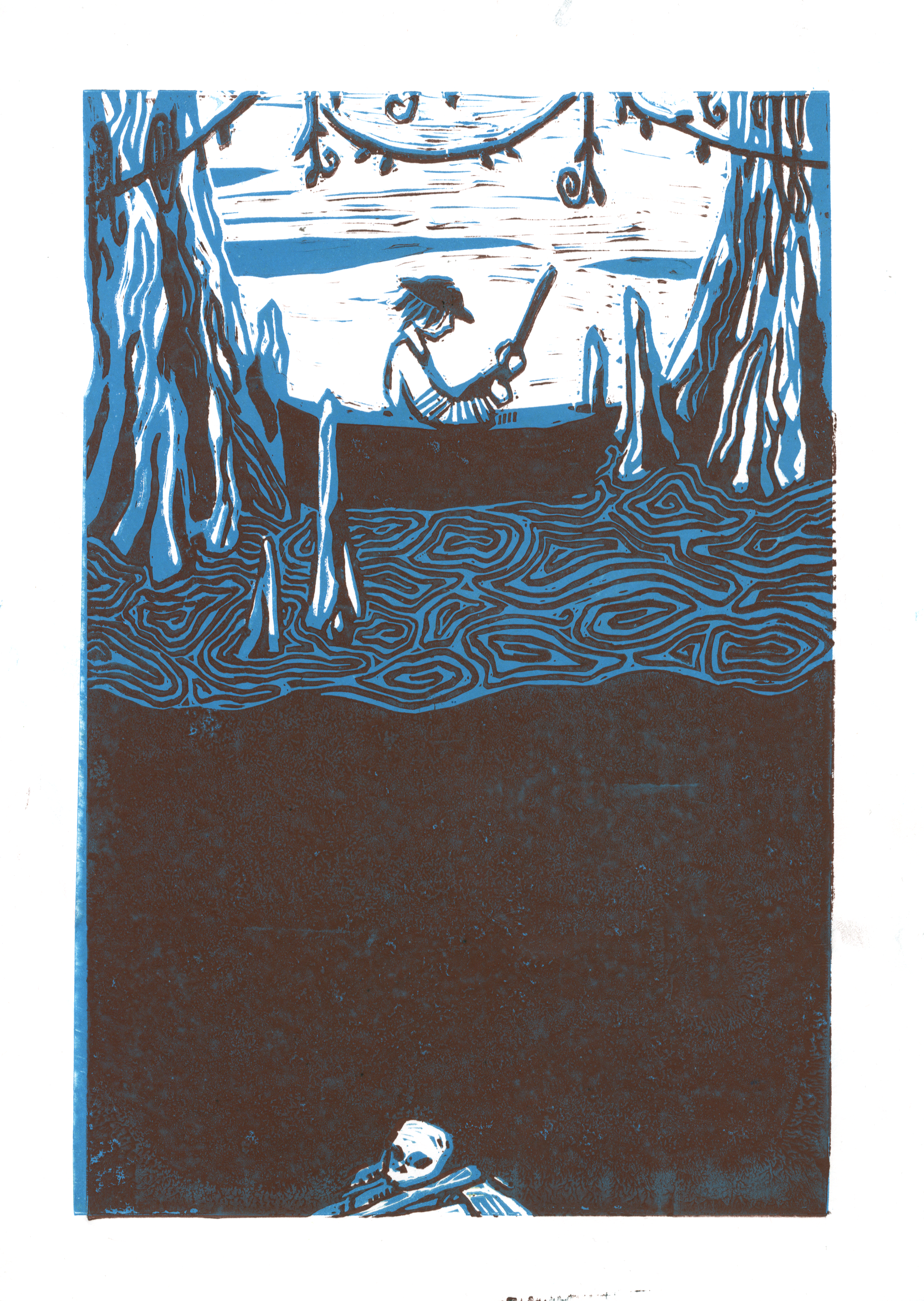

It was downright spiteful of the sun to shine so bright as we knelt in our little boats mourning Marie. Didn't it know that she loved sunshine, that it had been weeks since it was this hot, that she had probably died wishing the clouds would scatter to nothing? It didn't help that my mourning clothes were stiflingly hot, that the lace collar itched at my neck. The air was thick with humidity to the point that it felt like breathing soup. We all knelt in our little boats, watching the still brown water, listening to the priest wondering what could possibly have gone wrong, lamenting on how Marie was gone too soon. She was only twenty-one, he said. As if we didn't know that. She will wait in Heaven for all of us, he said. I wondered just for a brief moment if I would ever meet her there. I should have said a better goodbye.

Marie was buried in the swamp, between the knees of a bald cypress tree. "Buried" was a loose word for the unceremonious way we tipped her body into the fetid water and garnished the ripples with a strand of moss. I watched her sink and imagined poisons seeping out of her body into the holy gravewater. Her limbs softening to nothing, her bones settling among all the others down in the muck. I felt absolutely nothing until the small waves caused by her body made my boat start to rock and I had to properly sit down to keep my head from spinning.

At dinner after the funeral, I sat lonely at the head of the table. My father had told me in the morning that many people thought I had killed Marie.

"I would never!"

He frowned at my exclamation.

"Never," I repeated, forcing tears to well up in my eyes.

"It just isn't natural," he said. "She wasn't sick, and it isn't as though she had any enemies. She's -- was -- only twenty-one, for God's sake. And dead already!"

No one spoke to me as we ate. It was not a silent meal by any means, except for me. Whether they were leaving me to grieve in peace or out of fear of what they thought I had done, I wasn't sure. When my sister's husband poured his third drink of the evening, he raised a toast to Marie's life. When he clinked his glass against mine, he said, "Personally, I always thought you'd be first to die." I didn't say anything because I had rather thought the same.

That night, as I lay sleeping, the darkness overcame me. I had been dreaming of a foreign city, freezing cold; an icy bridge over a dark river; alleys I couldn't stop getting lost in, and it began to seep through every corner until I was standing in a totally dark room. Cold hands pressed to my shoulders and Marie's whispering voice said I know what you did, echoing through my mind. I woke up terrified. "It wasn't meant to end like that," I whispered in the predawn dark of my room, but I suppose she didn't believe me, because she came back every night.

A year after her death I visited the gravewater and sprinkled all that remained of her serum above where we had interred her. Forever young, I thought. How true.

I married again the following autumn, under an overcast sky and orange-brown leaves. My mother sprung it on me the day after the anniversary of Marie's death, as if a year of mourning was all I needed, with no time for freedom before I was sent once again to a world where I had to make decisions for two. My new wife was pretty, she was young, she looked just as unwilling to go along with the ceremony as I was.

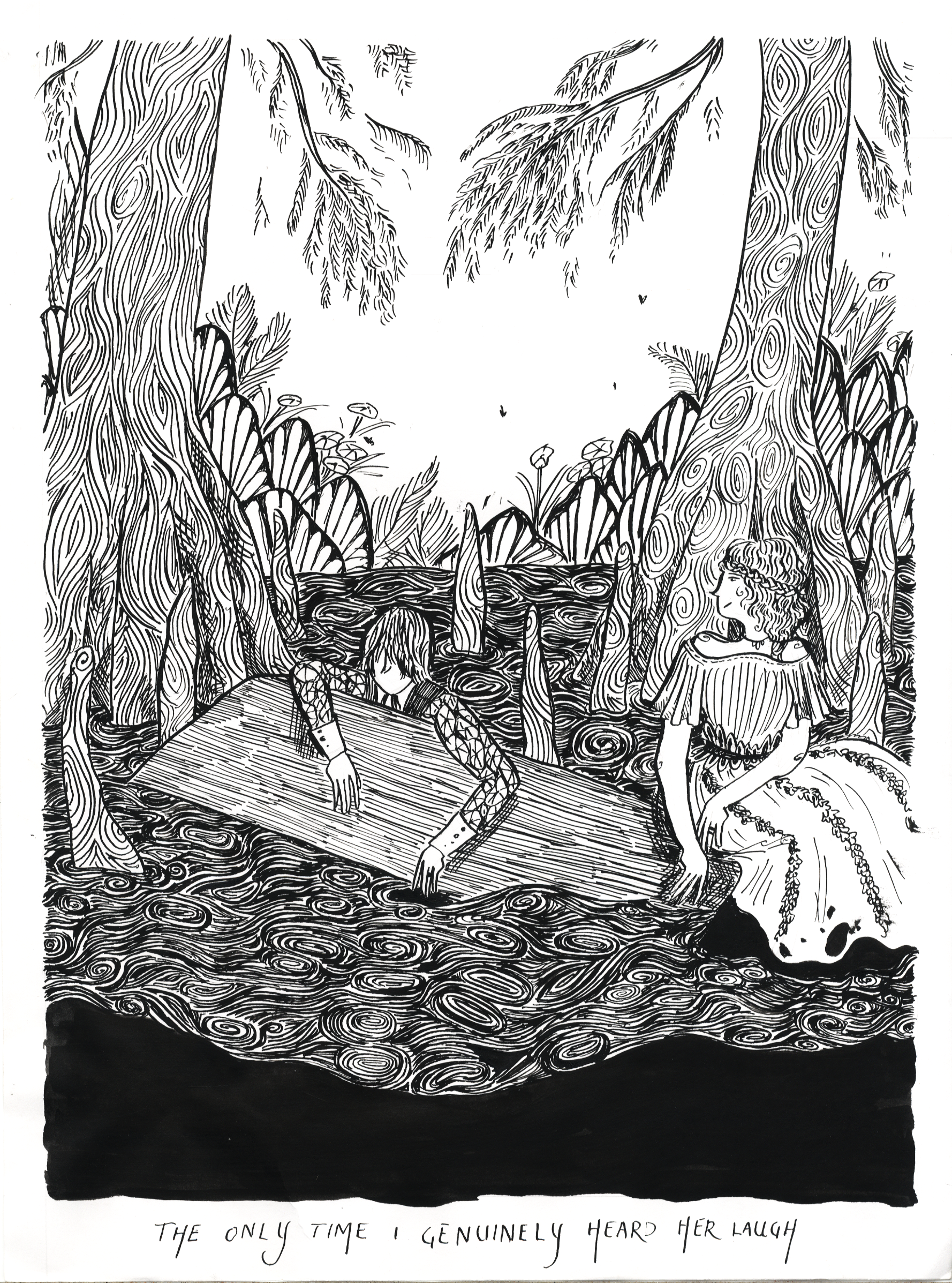

Suffice to say it was not the loveliest of weddings. With a wicked grin on her face that only I saw, she shifted her weight just enough to cause our wedding boat to topple into the murky water. The only time I ever heard her genuinely laugh was as she watched me gasp for air and pull myself, sopping wet, back onto the boat, which she had climbed atop as easily as an armchair. Her pale yellow dress was turning brown with muck, but she didn't seem to mind at all. Despite the fact that it was a warm day, I began shivering before we could complete our vows, and the second our obligatory kiss was over, rowed back to the dock as quickly as I possibly could to hurry through our maze of a manor and find new, suitable clothing.

I ended up wearing my funeral suit to our wedding dinner. The shivers didn't leave all evening, to the point that I considered excusing myself and setting a fire in my bedroom until my bones stopped shaking. Had it ever been so bad before?

As was traditional, my bride and I served one another a drink.

I wished just for a moment that I hadn't thrown away all of Marie's serum, to get my bride back for the ceremony. It didn't have to do anything -- the foul taste would be enough. As I handed her a glass of my favorite wine -- so boring, Marie said in my mind -- I imagined, just for a moment, her spitting it out in disgust, wrinkling her nose, having to excuse herself or perhaps choking it down miserably to avoid putting on a show. How satisfying that would have been! Instead she graciously accepted her drink and took a delicate sip, setting it aside and saying she wasn't much of a wine person. She handed me a glass of something, I wasn't sure what -- she had gotten up to mix it from a collection of bottles she produced herself. I took a wary sip, expecting something as disgusting as youth serum, but it was surprisingly quite pleasant.

I didn't trust her, even then.

When we retired that evening, she opened her dowry chest to reveal a bottle of rum and poured herself a glass without a glance at me or an ask of whether I'd like any. "Shall we toast to never touching one another?" she asked after her first sip.

I was taken aback. I hadn't much wanted anything to do with her, but I never would have been so blunt as to outright say it. "I've never met a woman so bold as you," I said.

"Not an answer." She took another slow sip and leaned back into the cushions propped up at the head of what used to be my bed and now was ours. "I can spell it out for you, if you wish. You are still far too addled by grief to bother with a new wife, and I am far too strange to appeal to you anyway. Or perhaps I am too reluctant and you feel bad doing anything to me. Or perhaps I can quickly dodge your grasping hands. Though you don’t seem like much of a grasper to me. Oh, well. Take your pick."

"I -- what?"

"I don't want anything to do with you," she said. "This entire union was my parents' fault, and considering that we were engaged practically as soon as your year of mourning ended, I assume it was your parents' fault as well." She waved her hand holding the wine glass through the air. "Would it be so hard to just -- act as though we have no obligations to one another?"

I did have an obligation, I thought. But only to myself.

And so the days sifted by.

Winter came and went, and as spring dawned on the horizon a cough settled into my lungs that wouldn't leave. The cypresses grew leaves once again, the swamp flowers bloomed bright yellow, and I spent days sitting in my little pirogue in an isolated little patch of water reading books and waiting for the clean air to clear my lungs. I'd been sick before, over and over and over, but never this bad -- lately the steps up to our manor from the docks had left me winded, laughing too hard turned into a coughing fit, and it wasn't uncommon to wake up in the middle of the night unable to breathe. My mother fretted over me. My father acted as though nothing was wrong. My new wife avoided me, citing that she did not want to catch my infection. "It isn't the sort of thing you catch," my mother explained to her, "He was born with it." She refused to listen, taking any excuse to pretend that I did not exist.

Until, of course, my parents caught wind of a peddler of miraculous cures who was in town for the next week. My mother had planned to send a servant to fetch something for me, despite my protests that I could go myself (I really couldn't at all, but I was desperate to leave the house, to leave the swamp, to see the colorful buildings and markets of town one last time -- I'd always been a terrible pessimist), until my wife suggested that she should go, all false sweetness and it really is my duty to help him.

If I had gone. If I had gone I would have told her not to buy a single thing from that man.

The medicine that my new wife returned with came in a small green bottle. "Five drops in your drink every night, that's what he said," she told me and my parents. "You'll be better than ever by the time it's all finished."

She made a show of carefully squeezing five drops into my wine. I made a show of drinking it -- or at least I tried to. With the first sip, a familiar rotten taste bloomed in my mouth, but I couldn't place it. I'd taken countless medicines in my twenty-four years; it could have tasted like any of them. I choked down the wine, familiarity burning a hole in my mind. What did it remind me of?

Two months passed. I took the medicine every night. Each time, that familiarity nagged at my brain, the memory of its flavor resting on the tip of my tongue. "It's so dreadful," I complained to her one night, downing a glass of water and medicine in one gulp. My cough hadn't much improved, but my new wife was insistent that it would just take time. It had, in fact, gotten worse, but no one listened when I told them that this new medicine didn't seem to work at all. Not that any of the others I'd tried worked much better.

"It's meant to cure you," she said with a grin, pulling our long, heavy curtains shut to block out the light of the full moon. "So you don't die quite so young." She had never disguised the fact that she thought I was at death's door.

Unbidden, the thought of a similar conversation nearly two years ago rose to my mind. "You never mentioned what it was made of," I said to my new wife, reaching for the bottle to take a closer look.

She pulled it away before I could reach it. It wasn't worth trying to take it from her -- she could dodge me easily, and the exertion would surely leave me hacking up a lung. Never mind that, though -- her reluctance was all I needed to confirm my suspicion: the medicine in the little green bottle tasted just the same as the youth serum I had once used to kill Marie.

Of course I had known what I was doing. I loved her enough, I suppose, but not as much as I had loved belonging only to myself. My life would be short enough as it was; why should I waste it trying to create an heir for my parents just because they couldn't manage to have more than one child? I wanted my own time, my own life, however long it lasted.

A little over two years ago, I'd heard tell of a strange peddler in town, selling all sorts of cures. I'd gone there thinking to find something that would help me: I was recovering from a nasty flu at the time, still sleeping ten hours a night from the fatigue despite the fact that I'd been "better" for four months by then. Marie and I had gone together, as I wasn't fit to make the journey on my own. Rowing a boat two miles into town was beyond me. She had been quickly distracted by a woman at the market selling exotic perfumes, and barely acknowledged it when I said I was off to find the healer.

His stall was a little cart, curtains wrapped around its edges like a fortune teller's caravan. "Are you the one with the miracle cures?" I'd asked, and he'd nodded without a word. I explained my plight to him -- all the illnesses I'd caught as a child, the way my body could never fully let go of the feeling of being sick even now. I just wanted to enjoy the little time I had, I said, even if my parents and my wife would outlive me by decades. I hadn't meant to say that last part; it just sort of fell out as I was explaining my symptoms.

"It seems to me that you have two problems," said the peddler. "I could try to heal your illessed, but truly nothing is guaranteed. Or," -- and here he stepped behind me and pulled the curtains of his cart closed -- "I could give you a little more freedom, no matter how long you live."

"What?"

"It's terribly unorthodox and even more illegal and it will certainly send you to Hell when you die," he said. "But. I can see in your eyes that you have often thought everything would be easier to deal with if only you didn't have other people dragging you down..."

"I'd be just as trapped with or without them," I told him.

"Tell me that losing just one person wouldn't make it better."

I paused for only a second: he had a point. Perhaps it would be just a tiny bit easier if I could have time to myself again. If all my days weren't filled with everyone worrying over my health. If Marie wasn't leaning over my shoulder every second of every minute -- "Maybe one."

"Just a tablespoon of this each night," he said, producing a blue bottle. "Two bottles will do it. Tell her it'll keep her forever young, and it won't even be a lie."

"Have you got anything for my illness, as well?" I took the bottles hesitantly. Did I really want to do this? "It'll seem strange if I return with nothing for myself..."

He handed me a small jar of fine grey powder with the promise that at the very least, it would prevent a cough. I bought it all with two gold coins and the feeling that I'd let my conscience get run over by a train. I found Marie again, still trying on perfumes, and said that I'd not only found something for my cough, but also a serum that would keep her young and beautiful as long as she lived, what delight!

I later wondered if she ever even considered that it was far more sinister than that.

There was no way I could tell anyone that my new wife was poisoning me. Not without admitting that I had poisoned Marie first.

"You know what I've just remembered?" I asked as she got into bed, adjusting the bolster pillow she'd put between us. "This medicine you've found tastes just like the serum my Marie used to drink to keep her beauty."

"That's the dead Marie?" said my new wife lightly.

"Well. Yes."

"Hm." She blew out the candle. I was sure she was smiling.

I stared at the ceiling, unable to keep myself from imagining my funeral. My new wife would sit at the front, watching as they committed me to the gravewater. She wouldn't say a word, but perhaps she would smile slightly, the way I had been afraid to do at Marie's funeral. My parents would say their words. Everyone in the audience would release a bated breath, not because they'd been eagerly awaiting this moment, not exactly, but they had been expecting it for a long time -- perhaps the priest had my eulogy written up and saved on a shelf even now, ready for whenever I breathed my last. My body and bones would sink to the floor of the swamp, mingling with all the others buried there over the years. Perhaps the bones of my hands would fall atop the finger bones that had once belonged to Marie. And only then would I apologize to her.