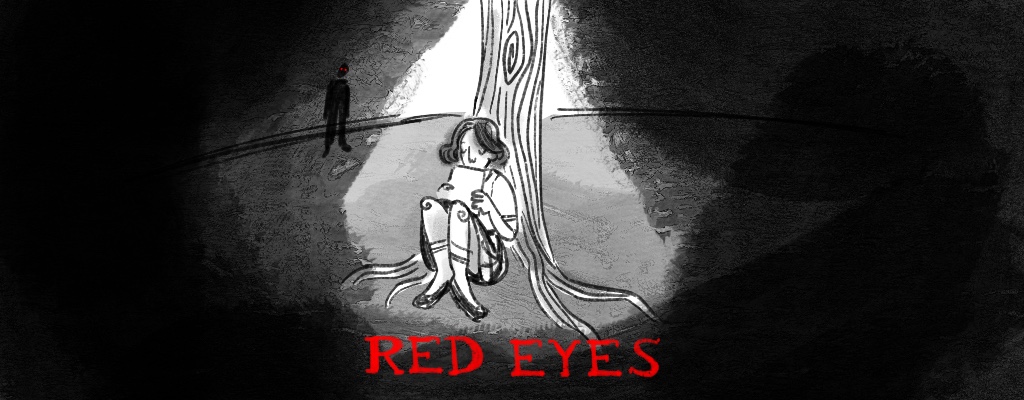

Red Eyes

Three weeks ago, my mother and I opened the door to two uniformed men, apologies falling off their lips as they stumbled and tripped over one another to tell us about the storm and the wreck and my brother. We're so sorry, we regret to inform you, he was far too young, but he was serving his country, we hate to say this... The Gloriana should have been able to handle the storm -- it was bad, but they were a state-of-the-art warship, we don't know how it happened, we wouldn't want to assume anyone left their posts but it's been a week without communications, we are forced to assume that everyone on board is dead.

"You waited a whole week to tell us that he disappeared," said my mother, her voice flat.

"Oh, um, well," blubbered the men. They told us that it wasn't Charlie's fault, that his transmissions had been spectacular, SOS SOS SOS with precise coordinates until they went raving mad and simply stopped as the ship blinked off the radar.

"Couldn't it be a blackout?" my mother asked desperately.

The men shook their heads. "We truly are sorry."

"By chance do you have the transcript?" I asked. "Just -- to read his last words..."

They hemmed and hawed and said they would think about it. It's confidential, they said, and he lost himself near the end, but we'll see what we can do.

When it arrived at our door, in an envelope my mother refused to touch, it still stunk of permanent marker, with only the strangest parts uncensored. Among all the S.O.S. messages, my brother would pause to ramble about red eyes, how he couldn't stop seeing them, how they watched him from every corner, from the faces of half the crew. They were there in the storm, and he was only safe in his cave at the heart of the ship, tapping out increasingly error-riddled messages.

THEY LL BE UPON ME AS SOON AS WE SINK STOP

I SEE THEM WHENVER I CLOSE MY EYES STOP

I M ONLY SAFE HERE IN THE BOTH STOP

SOS SO S

CAN YOU SEE TH RED EYES SPTO

THEY ARE NI THE WATRE STSP

IVE SEEN EHEM FOR MONTHS THEY ARE ALWAYS EHERE WHEN I BLINK STOP

SOS SSS

THEY GROW NEARER SOS SSS SSS EHE EHES EHEEYESSESU

The transcripts went on like that, progressively becoming less intelligible. The eyes were there, the eyes were always there, they were oh so red. At least, I was fairly sure that was what he was saying. His tapping had gone frantic towards the end, words morphing from ordinary English into a jumbled nonsense of E, I, S, and H, as if he couldn't waste the half-second it took to press a dash.

I considered showing it to my mother, but she refused my offer; it was tangible proof that Charlie was gone. She moved through our house like a ghost since the news arrived, mad with grief for my brother and fear for my father, flying high above the ocean, caught in the same war that had taken my brother. At the funeral, which I'd had to plan myself, all my friends walked on eggshells when they spoke to me, afraid that I'd lose myself the way my mother had -- how could I show them something as strange as the transcript? I read it over and over, as if the words would somehow change and reveal a clue as to if Charlie was truly dead.

And then I started to see the eyes as well.

--

I made excuses at first: I wasn't sleeping enough, I was worrying too much. I only saw the eyes when we happened to cross paths, they weren't following me at all. Or perhaps they were tricks of the light, my own paranoid mind mistaking cardinals in a tree, poppies upon lapels, as something malicious. But they were in the sky and the walls and more than anything, they were in the dark.

Who could I tell that I was going crazy? Certainly not my mother, who lived in her own mad little world, slogging through each empty day. She hadn't been to work since the news, though whether the airplane factory missed her or not was debatable.

Not my friends, either: since the news, we hadn't been ourselves around one another. None of us wished to burden each other with our grief, especially the one who had lost her twin brother to a bomb across the sea.

And certainly not Henry, my brother's longtime best friend who had lately begun miserably hanging around the house like a shadow we couldn't shake off. I wasn't sure why he spent so long with us -- none of us talked to one another. He soaked up my mother's grief as much as my own, letting it multiply his own.

The war began on my brother's sixteenth birthday. He counted down the days until he was old enough to enlist, eaten up inside by a desire to serve, the feeling that he was useless as long as he stayed home. He came home in tears the day he failed his physical -- curse those flat feet -- but the very next day we received a call saying they'd teach him Morse Code and install him as the wireless operator on a navy ship. Henry, on the other hand, had never shown interest in the war -- he was two months older than Charlie but ignored every letter imploring him to register for the draft, he told us his plans to sail to international waters in the event that recruiters came after him, he detailed the way he would purposefully fail his physical. He had no intention of risking his life, no matter what we were fighting: no war was a noble enough endeavour to die for, he said.

The last time he and my brother had spoken, it ended in a fight. It was two days before Charlie was due to ship out to sea, and they'd spent what turned out to be their last time together sequestered in the old backyard treehouse they'd built as boys. I had been outside weeding our victory garden when I heard their voices emerge from within, a sharp cry of "You'll die out there, Charlie!" and it had almost been a curse, a promise, because after all he had died out there.

After the news came, Henry began to spend his days haunting the shadows of our yard, scribbling in a black leather-bound notebook, staring up at the old treehouse he had inadvertently wished death upon his best friend of thirteen years in. He ate silent dinners with me and my mother, vegetable pies and bland canned meat. I set a place for him exactly where Charlie used to sit.

His family didn't like Henry's refusal to enlist, this much I knew, and surely that was part of the reason he hung around our place. He never said a word to me, and neither did I to him. Not until the day that the ship returned.

--

It had hardly been a month that Charlie had been gone, and it already felt like forever and ever. Perched on a rickety patio chair, I was reading over the transcript again, as if on the ten thousandth time the words would rearrange themselves into something that wasn't nonsense. This was perfectly healthy because I was out in the sun, I told myself.

THEY LL BE UPON ME AS SOON AS WE SINK STOP

THEY were the eyes, right? Had to be. There was nothing else they could be. But what were the eyes themselves? Charlie was rational. He wouldn't rave about demons pulling him to Hell or monsters clamoring at the sides of the ship, but the eyes were just strange enough to be within the realm of possibility. No human enemy would care about what happened to the sailors after their ship had sunk. Though perhaps the eyes were some new psychological weapon: what if Charlie's ship had been filled with a hallucinogenic gas? A poison that made them all go mad, that made Charlie start transmitting this nonsense. Something flashed red behind me. I turned back to the paper.

I M ONLY SAFE HERE IN THE BOTH STOP

Did the walls of the booth do something special to keep the eyes out? Why was Charlie safe there? What was he afraid of that made him have to hide? Perhaps I was thinking far too much of it. He could just be hiding from spies. From other ships. Submarines in the ocean below, carrying missiles that no ship would ever be safe from. God, I was never going to see my brother again, he was gone for the rest of time, and he was only nineteen. When had this happened, when had I started living in this world? Suddenly I found myself crying, something that had happened more than I was comfortable with the past couple weeks. I'd never been a crier before all this. But my brother was gone and my father was midair and for all I knew he could be shot down any minute, maybe he was dying right now and we wouldn't even know for another month at least, and it was just me and my mother and my brother's cowardly best friend against the world.

My head was in my hands, sobs echoing through my mind, hating that I couldn't stop crying, hating that I felt guilty over it. A tapping came on my shoulder, and I jerked up to find the aforementioned cowardly best friend watching me with concern.

"Ruth," he said.

"I'm fine," I told him, wiping my eyes which were surely red and puffy. I felt my face redden at the thought of him seeing me like this. "It's. Um. Charlie," I said, and that was explanation enough.

"Oh," he said. "Well. I'm going -- um. I've just heard -- your neighbor's at the door. And she says a battleship has just docked down at the waterfront."

"And."

"It's the Gloriana," he said. "At least your neighbor says so."

"No, it isn't."

"I'm going down to see it. I thought you'd like to come as well." It was the most motivated he'd seemed in three weeks, and that coupled with the fact that he'd never spoken to me before Charlie's death -- Charlie's disappearance -- made me decide to stand up, fold the transcript into my skirt pocket, and offer Henry a hand.

He did not take it.

We walked to the waterfront in silence. It seemed as though half the town was walking with us, though they surely didn't know how much this could mean. I reminded myself not to get my hopes up: most likely the name of the ship had gotten corrupted as it passed from ear to ear, likely it was just the Gloria or something similar. Charlie's ship could have disappeared halfway across the world, for all I knew, and it had disappeared. Ships that vanish from the middle of the ocean don't often come back. I started walking faster, forcing Henry to stumble to keep up. I pulled the transcript from my pocket and held it to my chest like a prayer. As the waterfront came into view, she rose up over the horizon: a huge battleship, all matte grey metal and guns tracing her sides. A red light atop the crow's nest blinked slowly at me. Almost like an eye.

Gloriana, said huge letters along her hull.

A horn sounded. Men filed out of the ship. Was this the way it was supposed to go? I wondered. If they had docked back at some naval base like they were meant to, would they descend the same way? But that didn't really matter. I found myself at the front of the crowd, Henry beside me, not really remembering pushing through it, and then we were staring at my brother and he was staring back at us.

At dinner the night the ship returned, Charlie wanted to act as though it were any other night and wouldn't answer any of my mother's desperate questions to try and make sure he was all right. "I'm here," he told her, and that was that. We ate casserole from the neighbors again. It wasn't any good, considering that it had spent two weeks in our freezer and butter was rationed, but even Charlie didn't complain about it like he would have before he left.

"How long will you be able to stay?" Henry asked. It was the least monotone his voice had been in a very long time.

Charlie did not answer.

He slept in his own room that night, but in the morning was gone, leaving a note that said he had something to attend to on the ship but would be back for dinner.

"I don't get it," fretted my mother after breakfast. "So long without us, and he won't say a word, and he instantly goes back to that awful ship."

"He's under contract," said Henry, who had spent the night over with Charlie. Something they hadn't done since they were very young. Neither my mother or I commented on it. "When you sign up they do all they can to keep you from leaving. You have to do what they tell you or they can ruin your life. He's got to complete however many years of service they told him to. They'll call him a deserter if he stays here."

A pair of red eyes watched from the garden. No one else saw them, or at least no one else mentioned them. I felt as though we were being spied upon.

"That's terribly unfair," said my mother.

Henry shrugged. "It's no more than I'd expect from the military."

He left soon after that, off to who knows where. Probably the waterfront, I supposed. The house seemed so empty without him -- to think we'd had four people at the table last night for the first time since the war began. My mother alternated between relief that Charlie was alive and woe that he couldn't just stay with us, and I found myself in the garden reading the transcript again. Charlie had not been in his right mind when he sent it, that much was clear. Did he still see the eyes? What would he say if I asked him about them? Even now, I felt their tiny pinpricks on me, a pair resting on the bird feeder, a pair hiding below the shed, a pair in the neighbor's window.

After the next dinner -- more half-warmed casserole -- I pulled Charlie aside and told him I had a question to ask. "Okay," he said, no more comments -- and I hated that, hated that I hadn't heard him complain or crack a single joke since he'd been back, as if the navy had done away with the brother I once knew. He wanted to pretend that nothing was different but he had forgotten how to act like himself.

"The storm," I said. "When the ship disappeared. We thought you were dead."

"What?"

"The officers gave me this transcript. From your wireless booth. They didn't bother censoring it because they said you'd gone fully mad."

"What are you talking about."

"But, um, oh, I'll sound so mad if I say this, you know the eyes you were talking about..."

"Ruth, go back. What storm?"

"Don't run off following him like you did yesterday," I said to Henry as I did the breakfast dishes the next morning. Charlie had stayed for breakfast and rushed out the door with barely a goodbye, and it had been all I could do to keep Henry from dashing after him. "Something happened."

"What do you want, Ruth. I could have walked to the ship with him and we'd have ten more minutes to talk," Henry said. "We're working things out. I think he doesn't mind that I won't enlist anymore."

I sincerely doubted that. "Look. When the officers came to tell us that he died, that he disappeared, they told us this whole story about how there was a storm, and a spy, and before the ship disappeared Charlie had gone mad... and they gave me this transcript from his transmission booth. And I tried to ask him about it last night, because, um, well, I thought I saw something. He didn't know what I was talking about. Any of it. He didn't remember a storm. The officers were quite sure that there was a storm. Even though they censored that part of the transcript..."

"What did you see?" Henry asked suddenly, practically hissing the words. It was not the reaction I had expected one bit.

"I feel like I'm being watched," I said, turning off the sink. "These strange eyes..."

"Red eyes," he breathed.

I dried my hands so I could take out the transcript, and Henry practically snatched it from me before I had the chance to unfold it.

"It started three weeks ago," he said without meeting my gaze. "The same night as the storm?"

I nodded. "Two weeks for me, but -- yes. That sounds right."

"They were after him. And now they're following us."

"I feel like we're focusing on the wrong thing here. I asked him about everything the officers told me and he didn't remember any of it. And then I asked him if anything happened three weeks ago and he couldn't think of anything. And then I asked him the date and he said it was the sixth of May. So." The storm had been on the eighth. Today was the thirty-first.

A pair of red eyes blinked from beneath the refrigerator.

"I have to go," said Henry, and he left.

Worse, he took my transcript with him.

At our third dinner since his return, Charlie was no longer silent, but he still didn't seem like himself. He wouldn't talk about where he'd been, said it was all classified, but he told a couple stories about life on the ship. My mother begged him to stay, saying that she couldn't handle the fear if he went back out, and he said that they were fixing something aboard the ship and they'd be gone as soon as possible, we should just take this time to enjoy while we can.

I picked at my casserole -- we'd finished the ham one and were now working our way through a potato and turnip one, which for reasons I couldn't fathom, somehow tasted better -- and watched Henry cling on every one of Charlie's words, no matter how dull they were. "This is hardly a step up from ship food," he said. "Mom, have you forgotten how to cook since I left?" and this was when I realized that bar my failed interrogation last night, none of us had told him.

"Helen down the road made this for us," said my mother. She paused. "The officers... they told us you were dead."

"Where did they get that idea?" asked Charlie. He sounded more flippant then, the closest he'd been to his usual self since he'd enlisted.

We all fell silent. "The storm," I said finally. "There was a storm, the night of May eighth, and you told them. There was a spy who attempted mutiny as well -- assuming the officers told us the truth -- and the ship disappeared off all channels after that...do you mean to say that you don't remember any of that?"

"It's the ninth," he said. "We were here on the eighth."

"It's the thirty-first," Henry told him.

"Oh, well, it all blends together at sea," said Charlie with a wave of his hand. As the wireless operator, even if no one else knew the date, he should have been dating his messages, I thought. I didn't say anything. "We've had storms, but none that bad -- I've never had issues with the wireless, so it must have been the other ships." He shrugged. "I'm not dead. Obviously." But his words were stiff and his shoulders tense and no one said anything for the rest of the meal.

I found myself doing dishes again, and when the sink was off, I could hear snippets of conversation from Charlie's room directly above.

"Look, none of that happened," said Charlie. "The officers must have lied to you; everything to do with the ship is classified, after all."

"I'm just conce -- confused. Look --"

It was quiet for a moment. I turned the sink back on and rinsed our plates. When I turned it off, Charlie was saying, "-- all nonsense, and they would never give something like this to someone like you anyway."

"They didn't give it to me, they gave it to Ruth."

"They wouldn't give it to a civilian, I mean. You're fixated on this way more than you need to be. Look, I'm still alive; isn't that what matters?"

"Of course it is -- but it's strange, don't you think?"

"Ugh, can we talk about anything else? Please, Henry, pretend nothing's happened. Pretend I haven't even gone to sea."

A minute's silence. I rinsed the silverware and switched to drying.

A thunk and a yelp of, "What are you doing?" This was Charlie.

Henry mumbled something I couldn't hear. Then, slightly louder: "Or have you forgotten that, too?"

"Of -- of course not, but don't you think -- you never know who can hear --"

A red eye blinked at me from the sink drain and I ran the water to flush it away.

"Oh, my God," I heard Henry say when I turned the sink off. "Your eyes."

--

The next morning our positions were reversed. I was cooking eggs and trying very hard not to think about what I'd heard last night because it opened up far more questions than answers. My mother was nowhere to be seen. Charlie had promised to stay for breakfast today so I was attempting to cook something nice, since there was no way our mother would. Henry appeared in the kitchen doorway and said, "Ruth. There's something wrong with your brother."

"Oh, what gave you that impression?" I said, annoyed that he hadn't listened to me yesterday.

"Last night," he said. "He wasn't himself...his eyes. Had gone all red. Like the ones I've -- we've been seeing in the shadows."

Charlie's footsteps came thundering down the stairs and both Henry and I looked up, startled. "Who knows what he's seen out at sea," I said dully, sure Charlie would be eavesdropping. "I'm afraid that the war has changed him."

"You aren't listening --" Henry didn't meet my eyes.

"When he leaves," I whispered.

Henry nodded. I flipped the eggs. He poured four glasses of orange juice. Charlie walked into the kitchen and we all acted as though nothing was wrong.

Before he left, Charlie said his commander did not like him spending so much time here, because it was terribly unprofessional and he didn't have official shore leave and none of the other boys on the ship had family in this town so it was kind of unfair besides. He'd try to come by for dinner -- it was leagues better than ship food -- but he wouldn't be able to spend the night anymore, you understand. My mother teared up at this, and I began to wonder if she was losing her grip on reality. I left the dishes for her because I had cooked and besides I'd done all the dishes for at least four weeks now, and when Henry offered to walk with Charlie to the waterfront I decided to tag along. Charlie shrugged and accepted but didn't seem very happy about it.

I trailed behind the two of them. Charlie said, "Don't you have better things to do than spend your time loitering around my sister?"

"I'm not -- she and your mother were the only ones who understood. When I -- when we thought you were dead."

"Since you refuse to enlist, I mean."

"I thought you were past that. I'll be going back to university in the fall."

"Studying poetry. Possibly that's worse. Anyway, I suppose I'm not against you talking to her. Maybe it would be for the better."

Henry turned around and flashed me a grimace. He lowered his voice. "If you ever realize you don't want to go back..."

Charlie stopped short. I nearly tripped into him. He stared at Henry. "You don't really --"

"We thought you were dead, I can't do that again! I knew it would happen, I told you so, and then you did, except I suppose you didn't die after all, but it's not the same as it was...you'll never get the war out of your head. It never will be the same again, will it?"

"You don't worry about anything real, do you, Henry?"

At this point they both seemed to remember that I was there, and started talking over one another.

"God, Ruth, I'm so sorry you heard all that, I forgot you were right there, he's just so immature --" Charlie.

"Sorry about that. He's a terrible lunkhead who won't look beyond what he's told to do --" Henry.

"-- and he seems to think we're still children, and he isn't ready to grow up, he thinks he can just do whatever he wants --"

"-- he truly can't think for himself, it's why he's fallen so deeply in love with the Navy, they tell him what to do all day --"

"-- no regard for the law whatsoever, or even common sense --"

"-- he doesn't care about the rest of us or even his life as much as his country --"

"He doesn't want you to die, Charlie," I said, because I couldn't think of anything else. "We were all so afraid when we got the news. It was terrible, and even though you're back and you're alive --" Probably, I thought, "-- we can't shake the fear that as soon as you're gone you'll die again, and don't say it can't be 'again' because you didn't die because to us you really were dead. He's scared for you, Mom's scared for you, I'm terrified."

"I'm going to walk the rest of the way myself," said Charlie. "I'll try to see you again before we ship out. They're nearly done with the repairs." For just a second, as he turned to stride away, his eyes flashed red in the morning sun. The air went cold around me: those eyes were more terrifying than ever before now that they belonged to my brother. Henry made a move to follow, and I pulled him back. We watched Charlie leave in silence.

"He's an idiot," said Henry finally.

"I don't think it's really him," I said.

"That was wholly and completely him."

"It's getting better, maybe, at pretending to be him. He died in that storm. Why would his ship turn up here? What a lucky coincidence for us. Why would they let him off like that? And I just saw his eyes, Henry. His red eyes."

Henry sighed. "I asked him about the storm last night. He said he still didn't remember any of it. I showed him the transcripts and he said they were fake -- to be honest, I almost believe him. Why would officers bother giving you the real transcript?"

"Oh, not you, too."

"I almost believe him. But there's something wrong. We were -- talking last night, and he's forgotten, well, everything. He's acting as though...no." He shook his head as if to clear his thoughts. "It's not just the being a bullheaded idiot. He's always been like that. I don't care about that. He's acting like we only met a few years ago, not like we've grown up together."

There was something he wasn't saying.

"And what was that comment about you this morning -- he's never been bothered by my -- UGH." Henry looked around, and said, "Can we go somewhere more -- less open?"

"What are you trying to do," I said, not following him.

He rolled his eyes. "I just -- don't want anyone to hear what I'm going to say. It's probably a terrible idea -- please don't say anything strange -- oh, I don't know how to say this," he said as we walked to the shadow of the seawall. Whispering so that I barely heard him over the crashing of the waves, Henry said, "I was -- we were in -- I loved him."

"You what?" I said. "That doesn't -- that's not how it --" But it did make a sort of sense. I thought of the way Henry looked at Charlie, the way he seemed to hang onto every word that came from Charlie's mouth, no matter how rude, the things I'd overheard last night. I looked back at Henry, his fingers twitching, his reluctance to meet my eyes, and realized he knew exactly what he was saying and whatever I was thinking, about how it didn't work and didn't make sense, probably didn't matter. "You could do so much better."

Something red blinked at us from the water.

"He doesn't remember it," said Henry. "I tried to -- um. To talk to him about it last night. He tried to play it off as concern about getting found out but it was like he didn't expect it at all. He's looked at me differently since then." He sighed. "You're right. I don't want you to be. But it isn't him."

--

We needed proof. We needed to figure out what to do with him. We needed an explanation. Most of all, we needed to figure out how to break the news to my mother. I laid these goals out to Henry and he had his doubts.

"She'll have to find out eventually," I said. "When he doesn't come back."

"But we can't tell her yet. She's too fragile."

I resented that he viewed my mother as someone so breakable but I had to admit that he was right. She'd barely been functional since the day the officers knocked on our door, and Charlie's return had, if anything, made her worse.

We were sitting in my room and I was acutely aware that this was possibly the first time Henry had entered it since he and Charlie snuck in when they were eight and I was seven and they threw all my toys on the floor and crumpled the homework I'd left on my bed. He was not so immature now. He sat politely on the stool at my dresser and I sat on my bed, and even though I knew there was no way he cared I still felt embarrassed that he was seeing such a private space.

"We'll have to figure out what to do about Charlie first, then," I said, and paused. "Not-Charlie?" A pair of red eyes watched us, reflected in the mirror upon my vanity, and I wondered if they could hear every word we said. "What he is. What he's done with Charlie."

Henry gazed out the window. I wasn't sure if he was listening.

"I think they must've replaced the whole ship," I continued. "They're fixing up where it was damaged in the storm, and maybe they'll head south to the capital and they've got some ulterior motive. They must have showed up here for a reason."

"You're being catastrophic," said Henry without looking up. "It isn't him, but maybe they don't mean any harm."

"You can't possibly think that they've taken over an entire warship just to do good. What happened to all your, ohh war is so evil, ohh the military hates everyone?"

"Sorry, excuse me for a minute," he said, and practically ran out my door. I heard the sound of retching from the bathroom.

For me, this whole situation was a puzzle, something that had finally dredged my heart out of the hole of grief I'd been wallowing in. I didn't know what I would do when not-Charlie disappeared. As much as I knew it wasn't him, it had taken my mind off the fact that Charlie was gone forever and ever, and -- it started to hit me then, and I shook it away. I could deal with that when his impostor was gone. Henry seemed not to compartmentalize so easily. I should go easier on him with this, I thought, but my brain couldn't stop buzzing with thoughts of the red eyes, of the thing that had replaced Charlie. I reached for the transcript in my pocket then realized that Henry still had it. Unless he'd given it to not-Charlie.

THEY LL BE UPON ME AS SOON AS WE SINK STOP

I SEE THEM WHENVER I CLOSE MY EYES STOP

I M ONLY SAFE HERE IN THE BOTH STOP

I didn't have the whole thing memorized, but those lines at the beginning wouldn't leave me. Charlie had known what was coming -- had he known the extent of what they were going to do, or only that he would die? He couldn't have possibly expected the eyes to create a new him, to take the ship to our town's harbor, to dock there as if just to torment me and my mother and Henry.

Perhaps I was catastrophizing, I thought. It was all very far-fetched.

When Henry returned, he was green and rested his head on my dresser. I felt bad and didn't say anything more about Charlie.

Charlie didn't show up for dinner that night. My mother was absolutely distraught. I couldn't bring myself to care, which was an odd feeling because I'd cared far too much about everything for the past month. I supposed I had to give it up for apathy eventually. Henry ate with us and didn't say anything.

"I can't believe him," said my mother. "He thinks he's above getting hurt, he doesn't understand what we went through, thinking he was dead. He thinks he can just leave without a goodbye. He doesn't care about any of us, and yes that includes you, Henry, just what does he think he's doing?"

Silence.

"And he told us he'd be back for dinner besides -- he doesn't care that we grieved him for weeks -- a mother should never have to grieve for her son -- I never should have let him enlist."

Silence.

My mother turned to her food -- quiche tonight, much better than casserole in my opinion -- and wept a little more. "And I know he isn't dead, really, but if we just let him go back out there nothing is guaranteed and he could die anyway. And he just doesn't care. As if the safety of the country -- no, I can't say that -- as if -- no..."

I looked at Henry as she said this. He didn't meet my eyes. A red flash from the window behind him did.

--

In the morning the battleship was gone.

--

It arrived at the capital that afternoon. I was the first to hear the news -- I was listening to the radio when a blaring noise cut through the middle of my favorite song and said, ALERT. ALERT. SHELTER IN PLACE. MORE NEWS AS IT DEVELOPS. The song resumed as if nothing had gone wrong, horns as jaunty as ever. I went downstairs to find Henry turning on the downstairs radio -- I hadn't realized he'd been here at all. On the news, the reporter described a battleship arriving at the capital unprompted -- a ship called the Gloriana. I wasn't even shocked: what else could it be? What other ship would end up there?

"You were right," said Henry. "They have some sort of plan."

A reporter explained the context to us: a battleship that had been presumed wrecked for nearly a month now had docked with no prior warning at the edge of the capital. No one had left yet, but we had to fear the worst: that it had been overtaken by enemies using it like a Trojan Horse to sneak into our country. We may have thought the war would not, could not reach our shores, but that was folly.

"But what is it?" I asked. "Listen: they're sending in soldiers as we speak. They'll be surrounded as soon as they get off the ship, and they'll never make it all the way to the government."

The reporter described the soldiers standing aside to allow the crew to file off the ship, and said that their blue uniforms did indeed belong to our country. He said that the ship was in fact still staffed by its original crew, and they did not seem hostile. He asked one of the army officers if he could interview some of the crew, and the officer hesitated but then said there was one who seemed harmless.

"I suppose we should start with an introduction," said the reporter. "I'm Jack Patterson, reporter for the National News Broadcasters. And you are?"

"Charles Evans, wireless transmitter for the Gloriana. Sir," he said. Of course it was Charlie. He probably hated that the army officer thought he was harmless.

"We're all a bit in shock about where your ship has come from, since it's been off the records and presumed sunk for the past several weeks. Are you allowed to tell us about that?"

"We dropped off the signal during the storm a few weeks back, and hadn't been able to get it up and running again since then, but last week we docked up north in a little town called Hogsbeach and were finally able to repair the ship," lied Charlie smoothly, as if just two days ago he hadn't thought it was the ninth of May.

"But why would you come to the capital?" asked the reporter. "Why dock in a small town? Why not go straight to a navy base?"

"Our navigation system was broken as well -- I was in charge of fixing it, but it was quite difficult with only the supplies on the ship. As for why we came to the capital, well, our commanding officer has a message for the President."

"Oh?"

"It's classified, I'm afraid -- I don't even know what it is, but I wouldn't be allowed to tell you if I did." We both heard the easy smile in his voice.

"It sounds just like him," said Henry.

"It isn't, though," I said. "It can't be. You saw."

"Let me pretend."

Charlie reassured the reporter that nothing had gone wrong, and the reporter thanked him for the interview. "We'll keep you updated as the story develops," he said, and then switched to talking about the weather. Something red blinked at us from inside the radio.

At that moment my mother came in from the front yard, where she had presumably been taking out her anger on the hydrangeas. "Why are you two listening to the news?" she asked.

We looked at each other, and Henry said, "Well -- um -- the ship -- Charlie's ship --" at the same time as I said, "The Gloriana docked in the capital."

My mother stared silently at the radio.

"Charlie was on the news," said Henry. I sighed, clenched my teeth, wished he hadn't told her that.

"What did he say?" she asked.

"The commander wants to talk to the President."

"And after that, he'll come home again?"

"How am I supposed to know. He didn't exactly go on a live radio broadcast and say, Mom, I'm coming home in two weeks, please be patient, he said that he was the wireless transmitter and the ship was lost for a month. He's at work, Mrs Evans, you know that. As much as we'd both like him to do anything else, he is contractually stuck with the Navy."

The radio blared that horrible ALERT ALERT ALERT sound and the reporter said in his perfectly measured voice, "There has been an update in the story of the Gloriana, the vanished battleship that turned up today on the banks of the river at our nation's capital. The ship's commanding officer was granted an office with the President -- shocking several aides -- apparently they knew each other as young men. I have one of those aides here to update us -- would you introduce yourself for us, please?"

We listened to the aide talk about how he thought this whole situation was strange and suspicious, and he didn't understand why the president would agree to talk to an average naval officer who wasn't even particularly decorated, whether they'd played baseball together in school or not. And then he said, "And they let that skinny little wireless operator in too."

My mother gasped in shock and possibly delight. "Charlie's meeting the President?" she squeaked.

Henry gaped at the radio, an inscrutable expression on his face. I was not thrilled at the progression of events, because who knew what this false Charlie was capable of. And assuming their whole ship had been replaced -- it was too awful to even think of. "Look, Mom, there's something Henry and I wanted to tell you," I started.

"Oh," said the reporter on the radio. "This is quite unusual -- I have just been invited to interview the President, what an honor, it'll just be a minute while I head inside, oh! We aren't going to the press room, truly? What an honor, what an honor..."

A muttered, "Would you quit chattering?" from the aide silenced him, and we listened to two minutes of dead air punctuated with the faintest sound of footsteps before a door creaked open.

"Here I am in the President's office," said the reporter. "I'm here with Mr. Ward, the aide you've just heard from, as well as the Gloriana's commanding officer and wireless operator, and of course the man himself! What an honor to broadcast your words from my very own microphone, Mr. President."

"You're very welcome, Mr. Patterson," said the President. I'd heard his voice before, when his speeches and debates were broadcasted, but it always shocked me how deep and scratchy it was. "I've invited you here to share the information that Admiral Moore has told me with the world."

"What an honor," said the reporter again.

"It's like he doesn't know how to say anything else," muttered Henry.

"Just a minute," said the aide on the radio. "Mr. President? Are you all right --" His next words were unintelligible.

"I'm fine, Ward. This is a matter of national security."

"Did anyone else see that?" asked the reporter.

"He really isn't very professional," my mother said with a frown.

"Your eyes, were they always that color? Mr. President?"

Henry and I turned to each other. His mouth gaped open, and I couldn't stop shaking my head. "Did what they said change him?" I breathed.

"It is crucial that I spread the message from the Gloriana with all of you, and this --" said the President, voice cut off by Henry unplugging the radio from the wall.

"What are you doing?" cried my mother. For once I privately agreed with her. "What if they had Charlie speak again?"

"It isn't Charlie," said Henry, voice completely flat. "And whatever he said was enough to instantly make the President trust him -- to change him -- there's something wrong with all of them, Mrs Evans."

"Of course it's Charlie!" said my mother. "There wasn't another wireless operator on that ship, and you said yourself that Charlie was just on the radio. There's nothing wrong with him at all. And suppose they were about to share important news? Suppose the commander went to tell him that the war's over?"

"It sounds like him, it looks like him -- the Charlie that just spent a week at our house wasn't him," I said.

"You two are absolutely mad."

"He was dead, Mom, he is dead, whoever we had for dinner all week isn't him. His eyes were red -- tell me you aren't seeing the red eyes even now, in every corner, just look, they're in the radio and they're in that crack on the ceiling and they're across the street under the neighbor's car."

"Are you seeing things?" my mother asked with a short gasp.

"Henry sees them too," I said.

"Leave me out of this," said Henry.

I stared at Henry, eyes pleading him to tell her the truth. "You're telling me he never sounded strange when we talked to him? Did you not think it was odd when he didn't remember the storm, when he thought it was still the beginning of May? He didn't sound like himself till the last day, he was still getting a handle on who he was supposed to be, it wasn't him!"

"The war changes people," my mother said. "I felt the same way about my father when he came back from the first war -- he wasn't as shell-shocked as the other men, but he still shook like a child during thunderstorms. Of course Charlie who came back won't act the same as Charlie who left, Ruth. That's how the world works. People change."

"That doesn't explain the memory loss," I said. "Or the eyes."

"People who go through horrible things often choose to forget them."

"I feel as though I'm crazy -- you aren't listening."

"You are the one who just admitted to seeing things," my mother said.

"She isn't imagining them," said Henry. "I really didn't want to say this. I've seen them too, Mrs Evans, and there's more, a, um -- a promise, yes! a promise that he made to me before he left. He's totally forgotten it. I wouldn't care if he broke it, but he was shocked when I brought it up to him two nights ago, as if it had never existed." Perhaps he would have been more convincing if he'd told her the truth about the "promise," I thought, but then again who knew how my mother would take it.

"What flimsy proof!" my mother said. "Look, Charlie is alive." She turned the radio back on, but it had switched to a play about two bank robbers. "What if he dies again, and you've just robbed me of my last chance to hear his voice?"

"The last time any of us heard his voice was when he left to enlist," said Henry softly. "We'll never hear it again."

--

The front page of the newspaper the next day was about the reappeared ship, and about a new order the president had passed, authorizing more bombs dropped, extending the war that we'd all thought was nearly over. A photograph of the ship was emblazoned across the front page, and the president's face, somber as he signed his order, watched us from the reverse. I was certain that I could see one color despite the photograph's grainy black-and-white printing, and the things watching from the trees behind me seemed to agree: in the president's eyes, the same color as Charlie's, as not-Charlie's, that rich, malicious red.